The highly influential American artist Chuck Close passed away earlier this month at the age of 81. His decades-long career showed longevity, even as his physical infirmities affected his style. Large-scale photorealistic works put him on the art world map. Later in life, his portraits using mosaic-style grids brightened subway stations and more in his native New York. It was a signature style that is always recognizable, always fascinating.

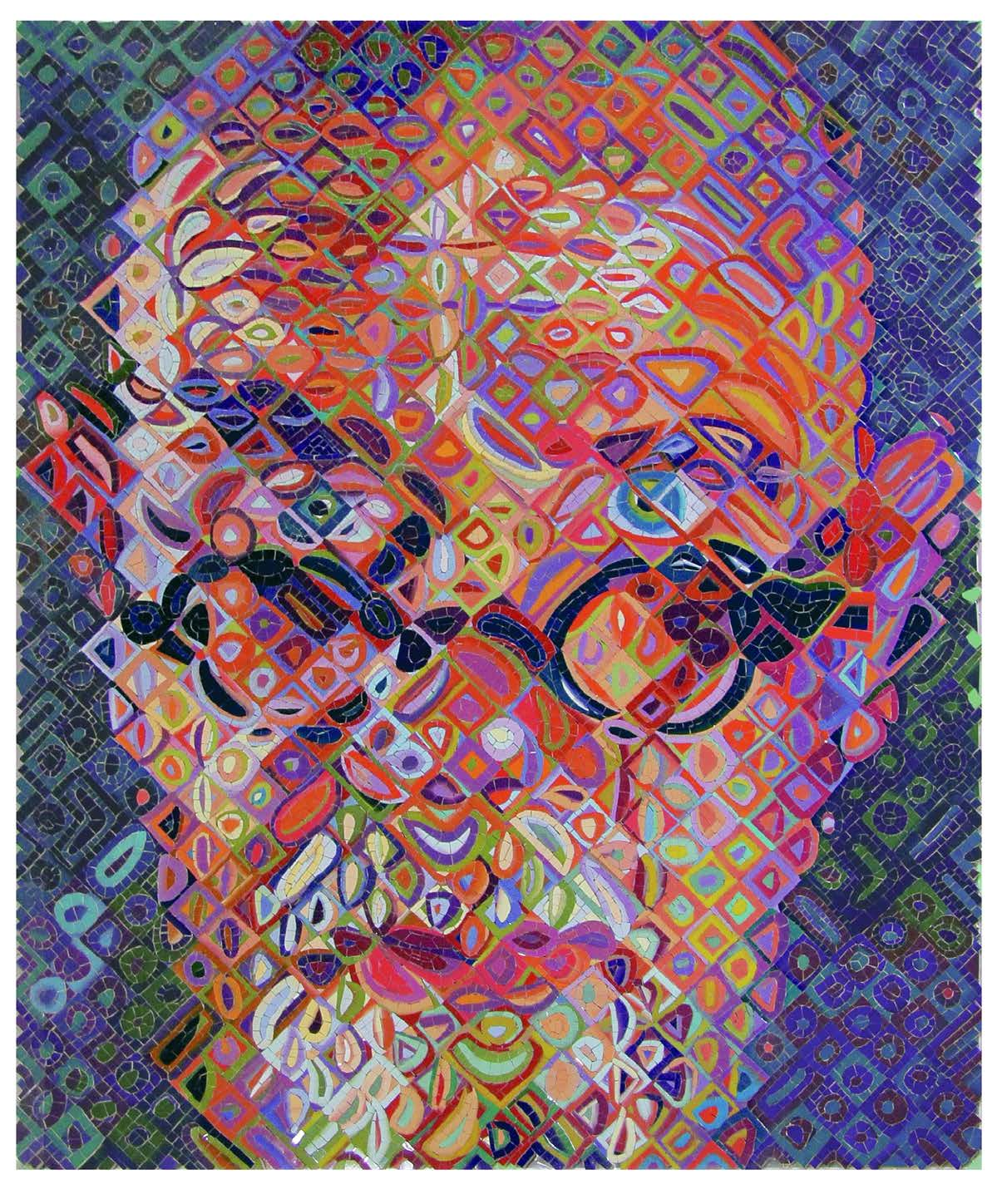

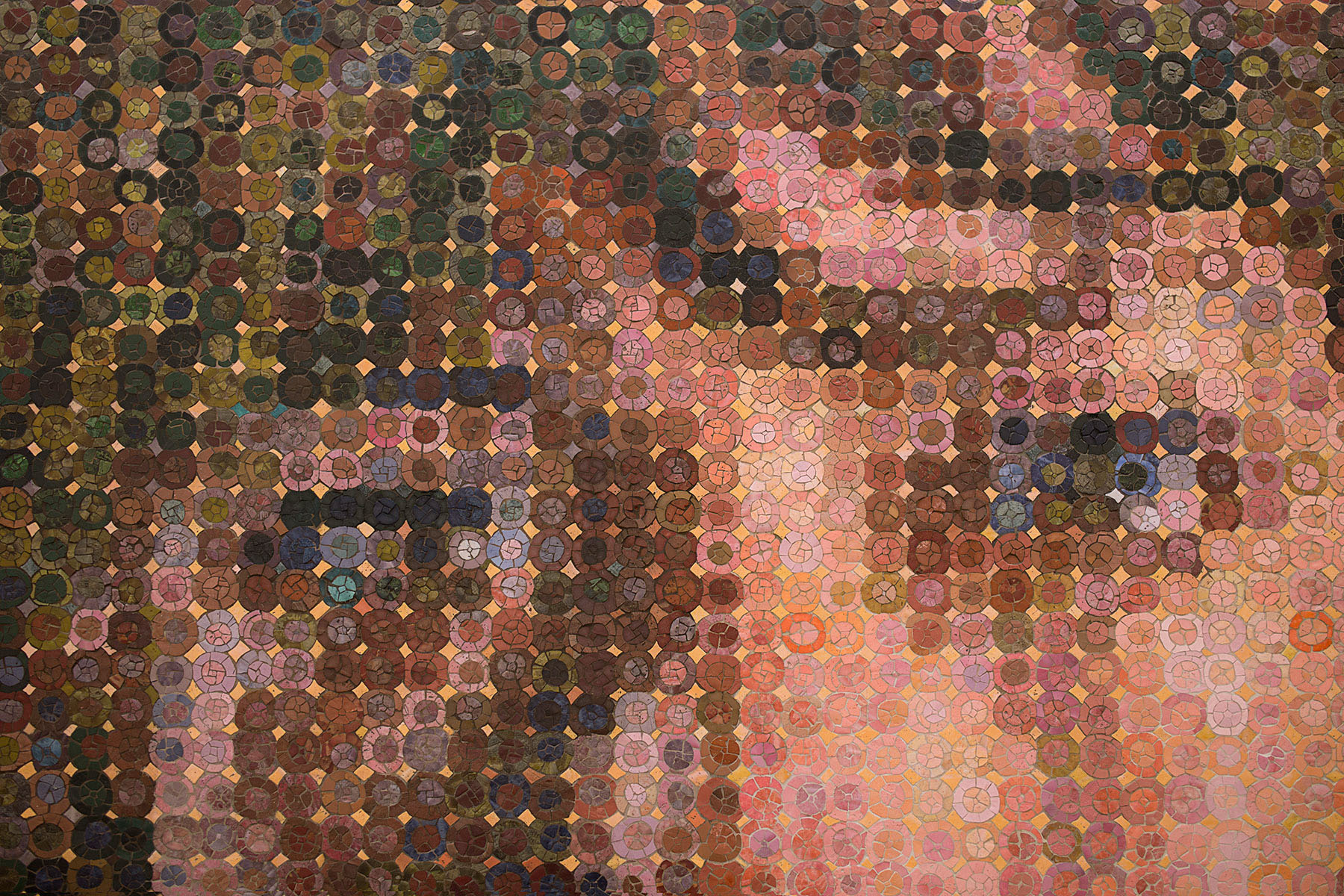

Close’s outsized reality lends itself well to the realm of public mosaic art. The immediacy of seeing a human face, stretched to gigantic proportions, is an arresting experience. At the same time, it’s a visual game. Walk to within arm’s length of one of his portraits, and the subject will dissolve into an abstract blur of individual squares. Back up, and the person appears, as detailed as a photograph.

It might be worth mentioning that Close suffered from a condition called prosopagnosia – face blindness. A quirk of the brain’s processing, it rendered him incapable of recognizing faces. Those with this problem can focus on details of a face – but there is no understanding of who the person is. For Close, his work-around was to change a three-dimensional subject into a two-dimensional photo or painting.

“Once I change the face into a two-dimensional object, I can commit it to memory. I have a photographic memory for things that are two-dimensional,” the artist once told the Society for Neuroscience conference in New Orleans.

When combined with his dyslexia, this worldview created an obsessive work style. Close was able to immerse himself into the individual sections of each supersized portrait, building the painted pieces tile by tile, as it were.

In 1988, Close suffered a spinal artery collapse that left him paralyzed from the neck down and confined to a wheelchair. During his subsequent rehabilitation, he learned to regain control of his arms and hands and continued to paint. He was able to strap the various brushes he needed to his hand and wrist, changing his brushstrokes to a looser style – but still hewing to his tightly controlled squares of paint.

One might argue that Close’s subway mosaic art pieces have exposed him to a larger audience than most popular artists. Each was site-specific and utterly arresting. Made of mosaic tiles, his style was translated perfectly into the language of tesserae and grout.

The collection was added to the 86th Street and 2nd Avenue Subway station in 2016. Close created twelve large-scale portraits, with his various painting techniques interpreted in ten works as mosaic art, and in two as ceramic tile. The subjects were diverse – representing the variety of individuals using the MTA system, as well as some cultural figures that were favorite subjects in his artistic career spanning over half a century – as well as two self-portraits.

For anyone who appreciates the art of mosaic, it’s both a revelation and an inspiration, to see the pieces in person. The details of the glass mosaic pieces are mind-boggling when seen first-hand.

To celebrate some of his final works, we’ll visit the installation.

Pozsi, custom-glazed ceramic tile

Self Portrait, glass mosaic tile art

Cecily – Tumbled Byzantine smalti tiles

Zhang, custom glazed ceramic tile

Sienna, glass mosaic art

Lou, Ceramic tiles

Cindy, custom glazed ceramic tile

Emma, custom-glazed ceramic tile

How did Close feel about having his works out in a world where people scramble by, thrown together by public transportation? Well, as he said, in an earlier interview, “It’s really no different from having a show in a gallery or a museum.”

Watching people rush by his portraits, Close told RealClear Life, “I want to say, ‘Wait, stop, look at it.’ But the pragmatism of an old student of art history won out for the artist.

“If you look at some subway stations … most of the mosaics have been on the wall since 1905,” Close said. “They’re not going away.”

Close’s work can be found in the collection of such institutions as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney, and the MoMA in New York; the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The artist received the National Medal of Arts from President Clinton in 2000.

To explore more artists and receive the latest stories we invite you to subscribe to our newsletter.